1968 salute leaves lasting impact on social activism in Olympic Movement

by Devin Lowe

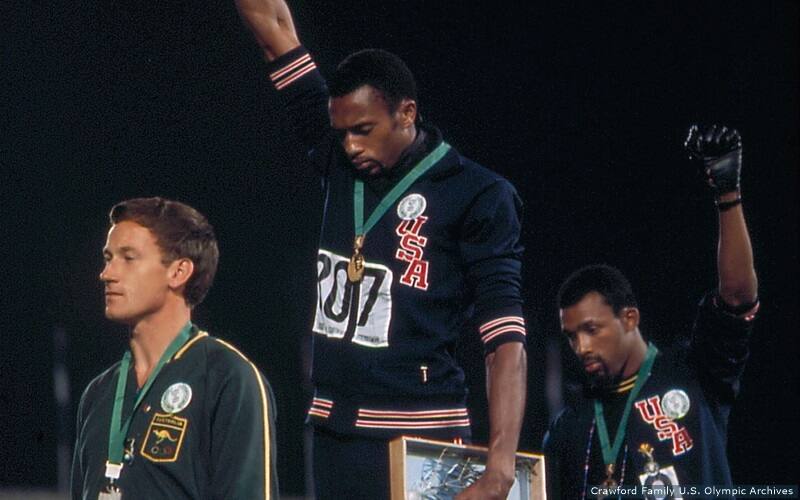

Tommie Smith and John Carlos raise their fists on the podium at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. Courtesy of the Crawford Family U.S. Olympic Archives, USOC.

Nestled in the Crawford Family U.S. Olympic Archives at the U.S. Olympic Committee’s Colorado Springs headquarters is perhaps one of the most famous portraits in Olympic history.

The year is 1968. The world has converged on Mexico City for the Olympic Games. And track and field stars Tommie Smith and John Carlos have just turned the apolitical ethos of the Games on its head.

In the photograph, two figures in navy blue track jackets stand atop a podium with their heads down and fists raised. They wear gold and bronze medals and a black glove apiece, two halves of a pair meant to draw attention to the plight of African-Americans back home in the United States.

“Getting on the victory stand, I had a heart feeling, but I didn’t have the words to prompt the necessity of revealing, verbally, what I felt,” said Smith, who earned gold in the 200-meter to place him on the podium that day along with Carlos, the bronze medalist, and Australian Peter Norman, who took silver and wore an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge to show his support for the protest.

“People didn’t believe that what I was saying was necessary, as far as equality is concerned. But now things are changing.”

Reflection spurs growth, progress

At the time, the reaction to Smith and Carlos’s gesture was swift and without sympathy. After boos and jeers rained down on the pair at the University Olympic Stadium, the International Olympic Committee ordered the U.S. Olympic Committee to suspend Smith and Carlos and send them home.

They endured death threats stateside. They were ostracized from the athletic community.

But almost fifty years later, Smith and Carlos have found their place amongst the Olympic family once more as history reflects on their salute with newfound respect and admiration.

In 2016, USOC CEO Scott Blackmun invited Smith and Carlos to Team USA’s White House visit and asked for their support and ambassadorship as the USOC works to strengthen its diversity and inclusion initiatives.

“He’s moving forward on diversity,” Smith said of Blackmun. “He’s moving around, spreading the word of greatness and goodness among people and especially the Olympic Committee … It’s just a direct 180 now.”

Carlos, who held a position on the organizing committeefor the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, called it an honor to meet Blackmun and to see his vision for the future of diversity at the USOC.

“For [Blackmun] to take the initiative to bring us back into the fold… I’ll always use the metaphor that he dropped the drawbridge and extended his arms and invited us to come across and be a part of the family again,” Carlos said. “It’s like a dream come true. Fifty years ago, my chances of coming here to speak to the Olympic family … it was never gonna take place in my lifetime.”

To the Olympic family’s benefit, Carlos was wrong about that. He and Smith were recently invited to Colorado Springs to deliver the opening and closing speeches to participants in the FLAME Program, the USOC’s hallmark initiative for diversity and inclusion catered toward college-age professionals.

While he was in town, Carlos toured the Crawford Family U.S. Olympic Archives, made possible by the generosity of USOPF Chairman Gordy Crawford. The Archives are one of the largest private collections of Olympic footage, photographs, artifacts and documents in the world.

Among the carefully preserved history, Carlos saw the moment that defined much of his and Smith’s lives — one that will serve as a living legacy of activism and courage at all costs.

“Perpetuity: I think that’s what’s in [donors’] hearts, and I think that spills over into the athletes of yesteryear,” Carlos said. “We’re thinking about perpetuity to the point where we want our legacies to live far beyond our lifespan.”

Smith has his own personal collection of memorabilia, some of which he has given to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. He intends to donate a few artifacts to the USOC, as well.

“We had someone who fulfilled a necessity to make a change, to do this so [the artifacts] can be preserved in perpetuity,” Smith said. “So long after I’m gone, people, athletes and citizens who are not involved in athletics can see that athletics has a very important place in our society. It’s an area of pride, an area of cultural involvement. It’s a whole world within itself.”

Leaving a legacy

The pair upheld their legacy as change-makers in the years following their 1968 protest. At Oberlin College in Ohio, Smith initiated the first women’s basketball and track and field programs. Carlos was a high school counselor and track and field coach for a time.

In 2008, they received the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at the ESPYs for their black-gloved gesture — 40 years after they were removed from the Games for the very same thing.

And as ambassadors for the Olympic Movement and for the peaceful power of sport, Smith and Carlos have closely followed the progress the USOC and the sporting world at large has made toward inclusivity and acceptance.

In many ways, their gesture was a catalyst for the changes they now see. It made people begin to think differently about diversity and why it matters, something in which Carlos takes pride.

“My father explained something to me one time. He said, ‘Son, I notice that any time your mother gives you and your brothers castor oil, your brothers will take that castor oil, but you always rebel against it. Let me tell you something: It doesn’t have to taste good in order for it to be good for you,’” Carlos said. “And I feel like what I did, in my history in track and field and the Olympic Movement and so forth, I was like that castor oil.

“Yeah, I taste bad, you didn’t like the flavor or the way I presented myself, but in the long run, you found that it made you a lot healthier down the line.”