Under leadership of Dr. Marc Philippon, Steadman Clinic boosts Masters, Schultz to top of podium

by Devin Lowe

Mike Schultz (center) and Oksana Masters (center-right) return to The Steadman Clinic with Julie Dussliere (center-left), vice president of U.S. Paralympics, and Kevin Jardine (left), director of high performance for Para alpine skiing, to show Dr. Marc Philippon (right) their medals from the Paralympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018. Photo by Eric Pond.

Mike Schultz (center) and Oksana Masters (center-right) return to The Steadman Clinic with Julie Dussliere (center-left), vice president of U.S. Paralympics, and Kevin Jardine (left), director of high performance for Para alpine skiing, to show Dr. Marc Philippon (right) their medals from the Paralympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018. Photo by Eric Pond.

A nasty slip on some ice in a parking garage could’ve ended Oksana Masters’ quest for Paralympic gold before it even began.

Two weeks before she was set to leave for South Korea, the then three-time Paralympic medalist was making final preparations for PyeongChang at a U.S. Paralympic Nordic Team camp in Bozeman, Montana, when she fell and landed on her elbow.

After the spill, Masters put off going to the hospital, hoping it might just be a pulled muscle. When she and her coach, Eileen Carey, saw the X-rays, they knew it was much worse.

Her right elbow was dislocated, the bone chipped. When Masters told doctors how many races she was planning on entering at the Paralympic Winter Games, they told her it was impossible.

“I literally think I lost five pounds from crying, because every time I heard ‘no,’ I just busted into tears,” Masters said. “Before the injury happened, I was having one of the best seasons of my life and I was chasing my first gold medal of the four Paralympic Games I’ve been to. It felt like my dream was right there, I was just about to touch it, and it was all slipping away.”

Enter The Steadman Clinic and the Steadman Philippon Research Institute, a world-renowned sports medicine and orthopedic center in Vail, Colorado. Three days after the injury, Masters flew to Vail for one last chance to hear “yes.”

“They took X-rays, MRIs, and they didn’t say this was impossible, or no. They said, ‘When are your competitions? When are you leaving? This isn’t gonna be easy, but we’re gonna do everything we can.’”

Between scheduled surgeries, the clinic’s Dr. Randy Viola did what he could to repair Masters’ elbow. He kept in contact with her and Carey to monitor her healing process, texting them a few times per day both during the team’s camp in Bozeman and when they arrived in South Korea.

“Dr. Viola believed this was possible, but it was definitely uncharted territory,” Masters said. “It’s not like I was trying to race one race. I was trying to race all of my events.”

Established by Dr. J. Richard Steadman, the U.S. Ski Team’s doctor in the 1970s, The Steadman Clinic has been treating athletes across the United States’ four major sports leagues as well as American Olympians and Paralympians since its founding in 1990.

In 2005, hip specialist Dr. Marc Philippon joined the staff as a managing partner, and in 2010, the pair founded the Steadman Philippon Research Institute, dedicated to orthopedic research and training doctors in evidence-based, innovative methods.

The Steadman Clinic is part of Team USA’s National Medical Network, a group of accredited centers in California, Colorado, Utah and New York that provide surgeries and rehabilitation to U.S. Olympians, Paralympians and hopefuls – at no cost to the athlete.

In the past year alone, the clinic has performed more than 80 pro bono surgeries for Team USA athletes.

“Money shouldn’t be an obstruction to their progress,” Philippon said. “All of our partners here in the group, we are all in agreement that we want to give back to our athletes. At least in that part, we can give them peace of mind.”

Alongside his work performing surgeries on sports stars from across the nation, Philippon is a trustee for the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Foundation. He says he is proud to offer both his time and financial resources to these athletes, who often return to the clinic with their medals and success stories.

“They have a lot of courage, dedication, discipline. For them, it’s truly about the sport,” Philippon said. “You see in their eyes the love for the sport that they’re involved with. I believe these athletes are in it for the excellence.

“I love to see them coming in with their medals. But the road to get there and the efforts and the sacrifices, helping them get through it, for me and for all of us here, it makes it worthwhile.”

Masters is one of a handful of athletes on the 2018 U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Teams to receive care at The Steadman Clinic. Another is “Monster” Mike Schultz, who has seamlessly bounced from action sports star to designer of sports prosthetics to Paralympian.

In 2015, Schultz underwent surgery on his right heel after shattering it in the adaptive snowboardcross semifinal at the Winter X Games in Aspen, Colorado. Three years after the injury sidelined him for six months, Dr. Thomas Clanton, who performed the reparative operation on Schultz, got to ski with him and his wife, Sara, when they returned from the Paralympic Winter Games.

“Anytime you’re working with athletes, your goal is to help them reach the highest level of their sport,” Clanton said. “I think it’s a really special group of people that competes at the Olympic and Paralympic Games … My gold medal is seeing the athletes that I’ve taken care of reach that level.”

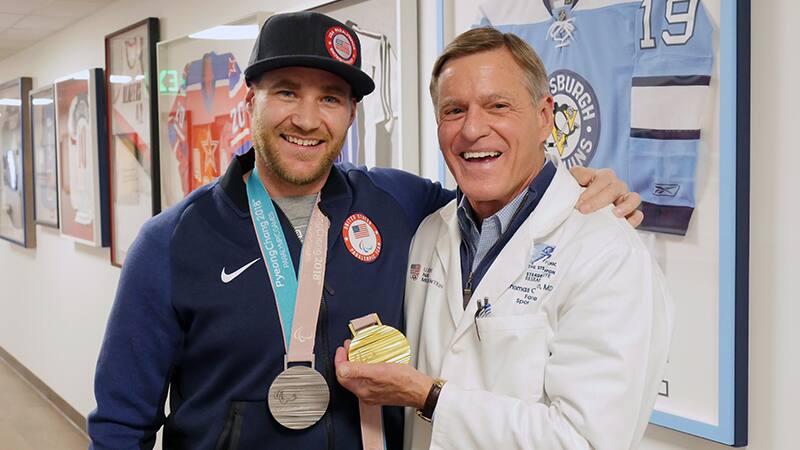

Mike Schultz (left) reunites with his surgeon, Dr. Thomas Clanton (right). Photo by Eric Pond.

Mike Schultz (left) reunites with his surgeon, Dr. Thomas Clanton (right). Photo by Eric Pond.

Chasing gold

The adversity Masters faced didn’t stop once she reached the snow in South Korea. In fact, during her third race of the Games, it heightened.

After winning silver and bronze medals in her first two races, the six-kilometer biathlon and 12-kilometer cross-country events, Masters fell in the mid-distance biathlon, reinjuring her elbow and forcing her to withdraw.

Medical staff took more X-rays of her elbow and delivered the news she was dreading: The injury could spell the end of her Games.

Still, Masters refused to quit. She and Carey kept in close contact with doctors at The Steadman Clinic as she prepared for her next race, the 1.1-kilometer cross-country sprint. She received treatment to help with the pain, still searching for her first ever Paralympic gold medal.

In the sprint, Masters fought her way to the front of the pack before overtaking her two closest competitors and building a sizeable lead on the final hill. With the lead on the straightaway, she looked over her shoulder and raised her arms in the air as she crossed the finish line, a Paralympic champion for the first time.

Her greatest feeling?

“Relief of being able to stop because it hurt so bad,” Masters said. “But it was also the feeling of, ‘Holy crap, I just did it.’”

Oksana Masters crosses the finish line in the cross-country 1.1-kilometer sprint to win her first Paralympic gold medal. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

Oksana Masters crosses the finish line in the cross-country 1.1-kilometer sprint to win her first Paralympic gold medal. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

Masters left South Korea with five medals, two of them gold, and Schultz earned gold in snowboardcross and silver in banked slalom. In April, they returned to The Steadman Clinic with their new hardware to thank the doctors that helped them reach the top of the podium.

“It was really huge to have not just the support here when you’re going through treatment, but also knowing they really, truly care about you and your dream,” Masters said. “They definitely own half of that gold medal, because it would not be possible without them.”

Winning Paralympic gold isn’t the end of the road for Masters. She hopes to qualify for the U.S. Paralympic Team in para-cycling for Tokyo 2020, which would be her fifth straight Paralympic Games. First, she has to rest her broken elbow, which required another surgery once she returned to the United States to repair the damage from her falls.

Masters says she wouldn’t have reached the pinnacle of her sport without The Steadman Clinic – and the Team Behind the Team.

“In some ways, it’s so weird to stand on the podium and be the only one there holding the gold medal, because you’re not the only one that owns it,” Masters said. “It’s the whole entire team behind you that got you there, that whole entire village of donors, sponsors, family and friends.

“Thank you so much to the donors. They’re the people that sometimes when you don’t believe in yourself and you’re thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, I can’t do this,’ they’re still believing in you and making your dream a reality. I don’t think a lot of people realize that the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Teams are not government funded, so all of our support for athletes and coaches, it’s the donors and the sponsors that are making that happen.

“I just want everyone to know that they own a piece of every single gold medal that Team USA brings home.”

Oksana Masters and Mike Schultz visited The Steadman Clinic and the Steadman Philippon Research Institute during Adaptive Spirit, a four-day event in Vail that gathers telecommunications professionals in support of the U.S. Paralympic Ski and Snowboard Teams. To make a gift to Adaptive Spirit that benefits athletes like Masters and Schultz, please click here. To make an unrestricted gift to the Team USA Fund in support of all U.S. Olympians, Paralympians and hopefuls, click here.